Fall 2020 - Behind the Issue - “Purple Haze?”

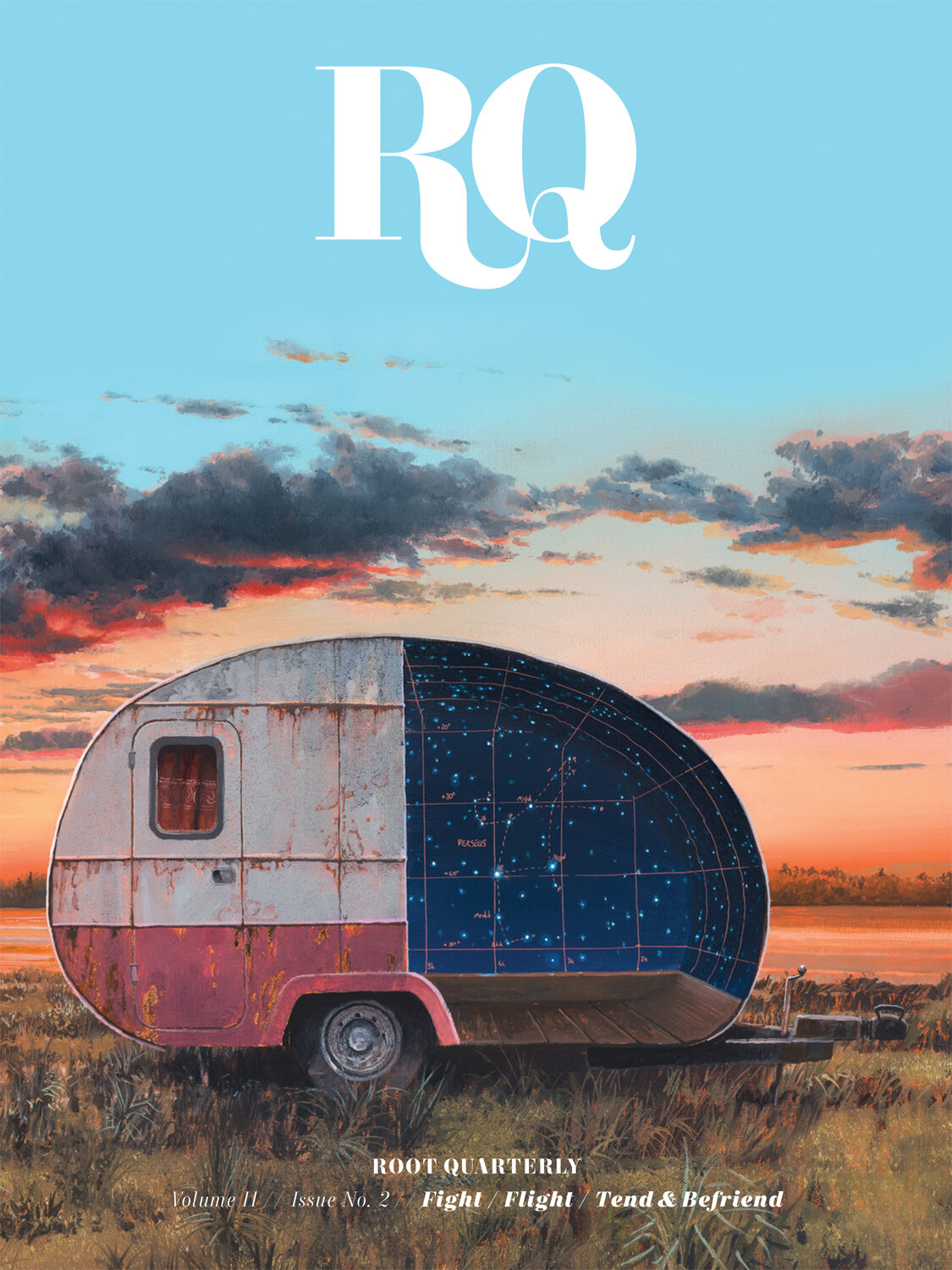

This article was sent to RQ readers and subscribers as a companion to Vol. 2 // Issue Two: FIGHT/FLIGHT/TEND & BEFRIEND. Purchase individual copies of the magazine and subscribe here.

Dear Friends:

Welcome to the fall edition of Root Quarterly. In our Fight/Flight/Tend & Befriend issue, we explore our theme in the context of our coming election and our heterogeneous populous. I hope you’ll permit me a bit of nostalgia on the way to a plea for more of us to think about how we can restore our democracy to working order, something I don’t believe we can do if we don’t deliberately depolarize ourselves.

Those of you who know me well know that I grew up in rural Pennsylvania in a town called Bloomsburg. It was an interesting place. While it was small and conservative, we also had a repertory theater and a University, a major research hospital just to our west, and a nuclear power plant flanking us in the town to our east. The latter is where my father, an engineer, worked as the plant’s assistant superintendent. He was one of the only men in the larger family that didn’t own a gun rack.

It was safe enough that I never had a key to my own house. Small enough that a good old-fashioned tractor pull might make the front page of the Press Enterprise, and that in our 100-kids-per-graduating-class high school, members of the football team also played in the band during half-time shows. Rural enough that my internship at the local vet included Saturday morning ride alongs for large animal visits, during which pipe smoke would fill the pick-up truck as we closed the distance between farms, where we would take good care of the pigs and cows that might one day end up on our dinner plate. The Great Bloomsburg Fair rose like Brigadoon each year in the fall, just about this time, bringing with it not only funnel cake but a farm show and freak show, as well as pre-dawn field-hockey practices under the lights on the football field. The school district shuts down for a week during the fair so the kids can work during the day—I did turns at Hewlett’s Hot Sausage and Roadarmel’s Rotisserie Chicken. I dug up deer bones alone in the woods behind my house, or rode my bike miles and miles down to the covered bridge by the river, and was allowed to know my own mind and find my own limits.

“The Great Bloomsburg Fair rose like Brigadoon each year in the fall, just about this time, bringing with it not only funnel cake but a farm show and freak show, as well as pre-dawn field-hockey practices under the lights on the football field.”

Idyllic, right?

It was a great place to grow up—as long as you were from there. Outsiders of any kind were not welcome. Some of the “Townies” did not much care for the University students and college professors that looked down on them from the top of the hill. When my now-bandmate Tracey, who is black, went there to college, she was shocked to be called the n-word for the first time in her life, repeatedly, and eventually transferred to Temple. As kids, we all heard hushed rumors occasionally that a cross had been burned in the night on someone’s lawn up in the hills (unconfirmed), and others that our favorite Main Street pizza shop was also a mob front (confirmed). A family of new arrivals from Norway had children, one of whom I dated, who were mercilessly and sometimes physically hazed and abused. When dear classmates and life-long friends of mine came out as gay our senior year during our production of “A Chorus Line,” it was likely dangerous for them to do so, but, courageously, they did.

“As kids, we all heard hushed rumors occasionally that a cross had been burned in the night on someone’s lawn up in the hills (unconfirmed), and others that our favorite Main Street pizza shop was also a mob front (confirmed). ”

After the 2016 election, I was asked by a former teacher to spend a day at the school talking about media bias and civil discourse, and I could not believe my eyes when I walked into the building and found a display in the hallway celebrating the Stonewall Riots and gay rights. (This is not usually what people mean when they talk about Pennsylvania as a “purple” state.) I talked with the kids all day, and, after school, with the “Students for Social Awareness” group. It was mostly women, and not a few people of color, asking advice about how to answer prejudice and to do good in the world. A young Latina woman asked what to do when someone would say to her, “It’s cool that you’re the first Latina Homecoming Queen,” because she wanted to be just the Homecoming Queen. I found it interesting that she would ask me, a white woman, what to do in this very particular situation I had never experienced, but I quickly realized I’d been thrust for the day into the role of everyone’s older sister (or perhaps the crazy auntie from the city), and so I did my best on the fly: “Remember that’s about them, not about you.” It seemed to work.

A lot had changed in the 24 years since I’d graduated, and not just that these young people were talking openly about racism, or gay rights, or that cell phones were everywhere: These kids also clearly had parents who were vocally either Republican or Democrat, and it meant something about who they were and what they believed. I don’t think I could have told you my parents’ political affiliation growing up—though they would take us with them to vote at the Firehall and I distinctly remember voting for Jimmy Carter inside a refrigerator box voting booth in my elementary school.

“I don’t think I could have told you my parents’ political affiliation growing up—though they would take us with them to vote at the Firehall and I distinctly remember voting for Jimmy Carter inside a refrigerator box voting booth in my elementary school.”

Many kids now, kids in the swing state I live in, are growing up in a time when a political affiliation—something that can and should be critically examined from time to time as your party’s platform and your understanding of the world changes—has turned into an unmovable component of tribal identity. That’s dangerous for all of us because it dulls critical thinking and open inquiry, which are key to a functioning society. These are skills that, as they atrophy, reduce us to slinging memes at one another in social media apps that only care how much attention and information we give them to sell to corporations. It’s especially dangerous when guns are ubiquitous. We’ve already witnessed Americans killing each other as a result, and we must pull back from that as a norm.

I started Root Quarterly in part because I strongly believe that we need to talk with people we disagree with, and learn to “steel man” instead of “straw man” their views in efforts to understand one another and try to find common ground. Most Americans believe in gun control, for instance, but not if you tell them you want to abolish the 2nd Amendment or the police department. What words we use and how we use them matters—listening in good faith can be the only start of those kinds of conversations.

I no longer believe that we shouldn’t speak with family about politics to keep the peace. I also think it’s madness to tell someone to cut themselves off from their family or the community they were born into if they hold differing views, even ones we find odious. Who else is better positioned to be persuasive with them?

“I no longer believe that we shouldn’t speak with family about politics to keep the peace. I also think it’s madness to tell someone to cut themselves off from their family or the community they were born into if they hold differing views, even ones we find odious. Who else is better positioned to be persuasive with them?”

If we hermetically seal ourselves into a filter bubble with others that agree, the oxygen runs out eventually, and I believe we are nearing that time. I told my father several years ago that if he and I, who do not usually vote the same but love one another, can’t speak civilly about politics, then we cannot expect Congress to. We cannot expect it of the next generation. And then what, exactly, is America? RQ is an intentional place where these kinds of conversations can happen, and I’m grateful you’re here. I hope you’ll tell a friend—we need a different kind of army to keep the peace.

Heather Shayne Blakeslee

Publisher // Editor-in-Chief // Root Quarterly

This article was sent to RQ readers and subscribers as a companion to Vol. 2 // Issue Two: FIGHT/FLIGHT/TEND & BEFRIEND. Purchase individual copies of the magazine and subscribe here. This is issue contains an interview with John Wood Jr., a national ambassador for Braver Angels, a depolarization organization.